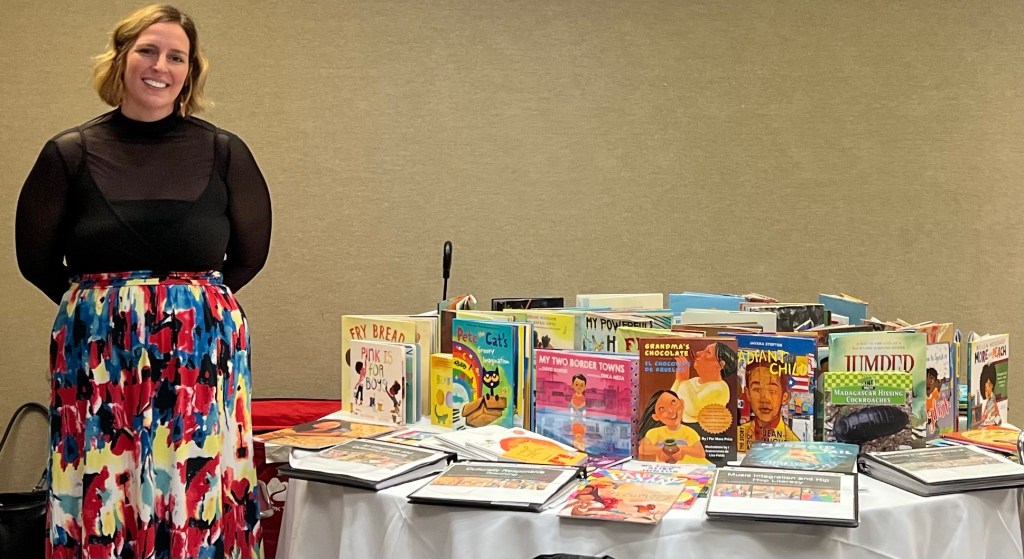

In the summer of 2024, I returned to the University of Northern Iowa’s third Literacy Initiative Cohort. This time, I was serving as a coach to the incoming group of educators along with three of my second cohort colleagues.

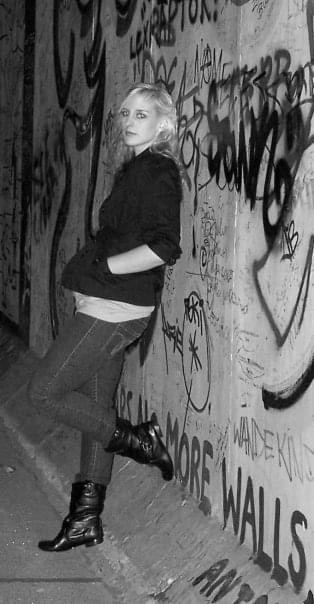

A lot has changed since I spent the summer on campus in 2023. My life has been transformed by the powerful experience of the UNI LI. I no longer feel like a passive educator swept along with the unpredictable current and whims of educational trends and policy, afraid to share my own perspective in teaching. I no longer feel surrounded by the walls of administrative decision making that silenced my voice as an educator.

In a time where educators are facing a fair amount of oppression, I’ve surprisingly managed to find an oasis of freedom.

I now feel empowered and trusted with my thoughts and instincts as an educator. I know my colleagues feel the same way. I also have a new career and role in empowering future educators and shaping the future of education.

And with this empowerment, came a year of accelerated growth. I led a team of new teachers in a pilot preschool program. I incorporated hundreds of diverse books into my teaching. I embraced cultural pedagogy and advocated for equity. I built a lifelong love of literacy using quality daily read alouds and the Mock Caldecott. I shared the joy of music and art daily with my students in engaging and innovative ways.

And of course, my preschool students and I had the joy of exploring Hip Hop Literacy or “Floetry” as Dr. Shuaib Meacham recently defined. Floetry is a rhyme that flows like poetry and can be rapped. As my preschool students do not yet have the skillset to write and revise their hip hop, they composed “floetry” and wrote spontaneous songs in the moment. I was anxious to share this experience with the new cohort on the fourth day of our initiative.

I was especially excited for the day of Hip Hop Literacy as Dr. Meacham had something extra special planned. Educators were going to experience writing Hip Hop Literacy themselves!

Dr. Meacham also had another surprise. Some special guest visitors.

At the front of a room of Iowa educators, a family of four was seated. A man and a woman, and their two daughters.

The family shared the joy hip hop literacy had brought them and their child. They attended Hip Hop Literacy through their church in Waterloo, Iowa where Dr. Meacham organizes youth Hip Hop. The parents shared what the experience has done for their child’s confidence and how endearing it is to see the older children helping the younger children write hip hop. Then their child shared some of her hip hop songs.

It was a very powerful moment. Her songs were beautiful and important. We saw ourselves in this family and perhaps began to see hip hop as something we could do with our children and students. I found myself pondering how seeing others do what you have a hard time imagining yourself doing really does matter. Perhaps this group of Iowa teachers would better see hip hop as something they could incorporate with students because of this experience.

Next it was time to write! Dr. Meacham had very clear and concise instructions for how to compose Hip Hop Literacy. We worked alone, paired up, or formed small groups to write our hip hop song on any topic we felt passionately about.

We coaches first made sure everyone had mastered the technology. While doing this, I walked past a room of a teacher working intently on her song. Another group of teachers were passionately sharing ideas. Another couple were sitting side by side and didn’t even notice as I walked by. I decided to give them their space and go encourage the coaches to write as we did not get to experience writing hip hop last year.

And we did! Nicole Robinson and I wrote a song together with mostly improvised lyrics and a few scripted lyrics Nicole and I wrote together. Nicole was vital in helping troubleshoot the technology and I was thankful for her help. Gretchen Goltz Conway worked intently on her own and did not need any encouragement from anyone. I was excited to see what she was working on with such focus. I encouraged Kathy Feltes to write and she protested saying she wasn’t a hip hop writer until I told her to just write about chocolate.

When we all came together, we uploaded our song files into a Google folder and played them over the classroom speakers. Nicole and I created the stage name KNick and shared our song, “Play” which Dr. Meacham said it reminded him of “Floetry”. Darcie Wirth took the artist name, “Purple Phoenix” and shared a powerful song of personal growth. A pair of veteran teachers, Amber Junk and Amy Sikora, had us laughing with their version of, “Ice Ice Baby” titled, “Lit Lit Baby” which contained the UNI LI relatable line, “To the extreme we collect books like an addict, now pick up your book and read like a fanatic!”

One teacher shared a song so breathtakingly vulnerable I was moved to tears. Kathy shared her perfectly imperfect and unfinished song about chocolate. Then it was Gretchen’s turn.

Gretchen gave a disclaimer that her song contained expletives and made sure that was ok with everyone before her song was played. That got our attention. We then heard an unforgettable song, “Get Outta My Body”, about Gretchen’s battle with cancer. The expletives stung and stuck like daggers dipped in alcohol; they were the very best words to depict the hell that is fighting cancer.

It was quiet for a moment as the power of the song swirled the room, hanging in the air like an icy fog. UNI Professor Marissa Schweinfurth commented that we knew Gretchen would beat cancer and that we were all looking forward to hearing the remix. I shared my suggestion for the remix title: ”Try it again, B****!”

After everyone felt the joy of creating hip hop, I shared my experience incorporating hip hop with my preschool students.

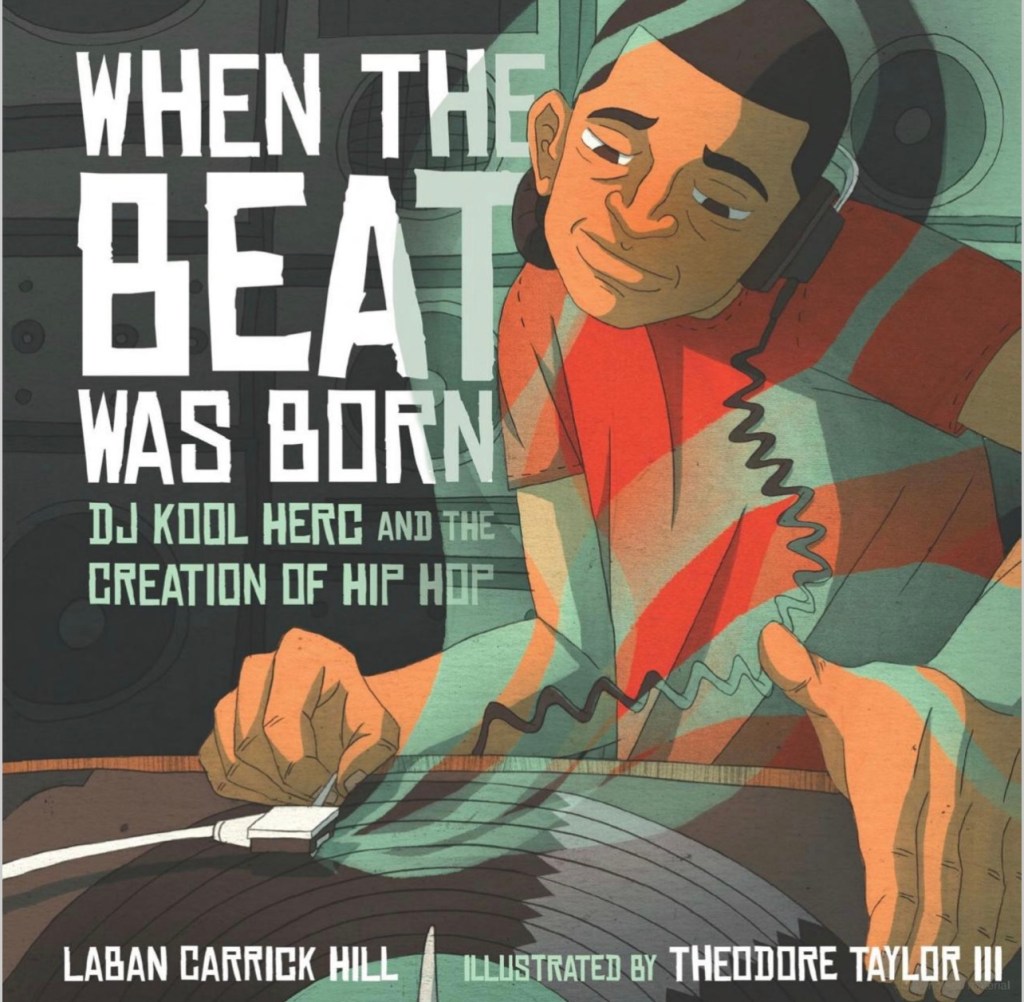

I shared how reading, “When the Beat Was Born: DJ Kool Herc and the Creation of Hip Hop” opened my eyes to the power of toying with our ideas. DJ Kool Herc was just playing with his voice, turntables, and announcing artists when he started to feel that he was onto something. He took that seed and planted it, tending the soil, watching it sprout and supporting its tendrils as it grew and changed shape. In that opportunity for space for play, he invented an entire genre of music that continues to shape society to this day. That’s the power of giving students opportunities to create: when creating, they’re always on the verge of discovering something completely new and transformative. Whether they’re an immigrant working in a club in the Bronx or a boy growing up on a tenant farm in Iowa.

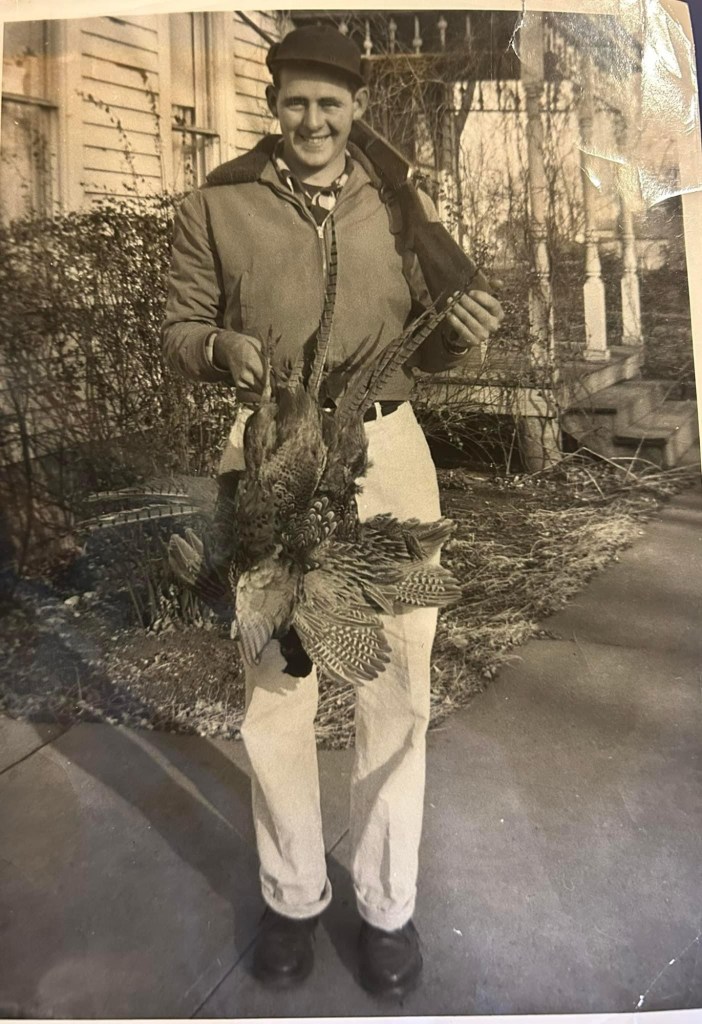

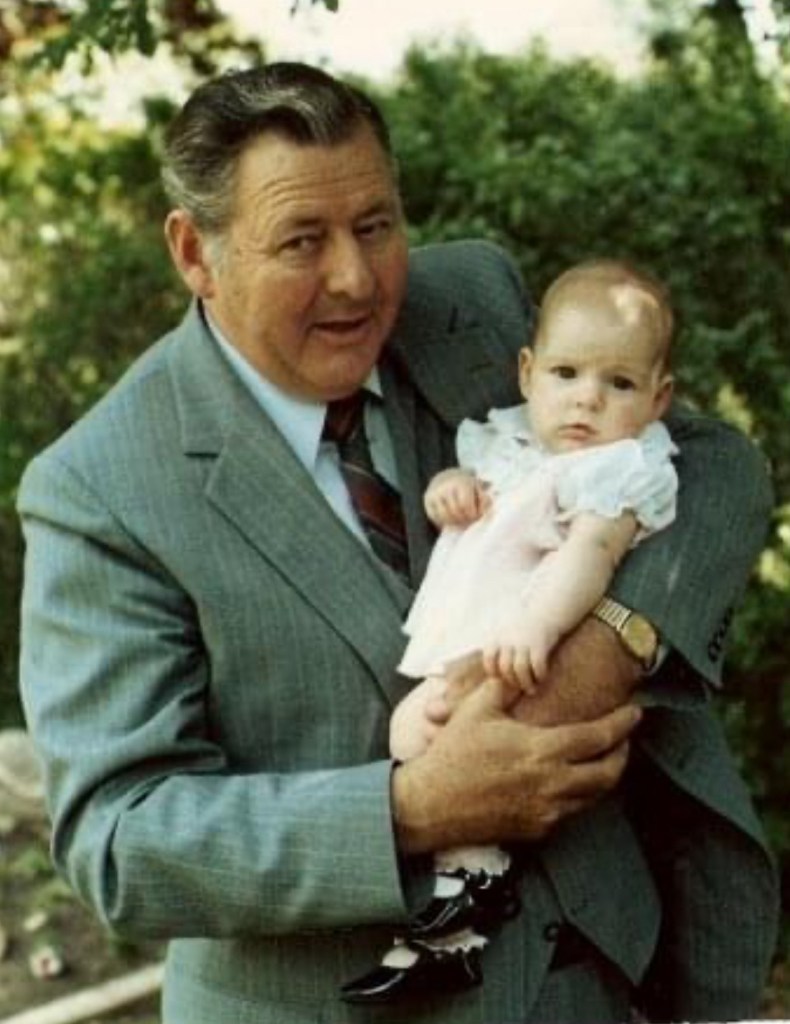

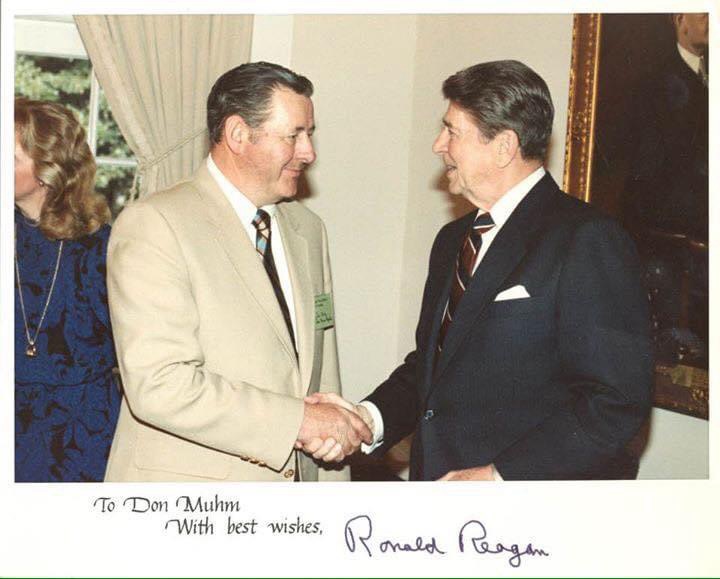

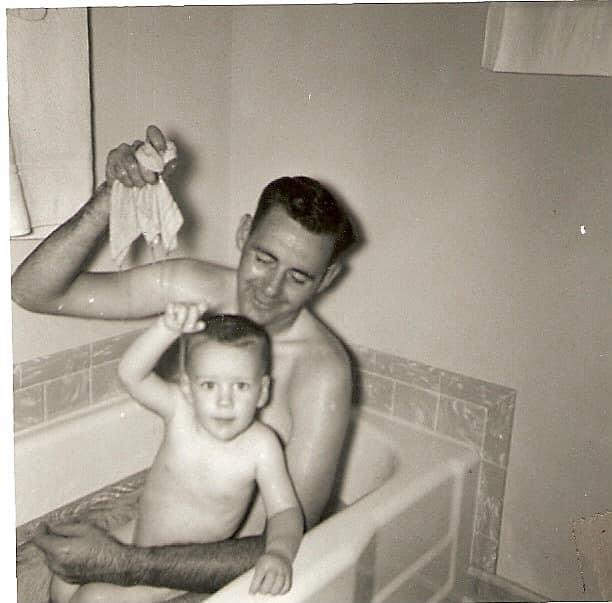

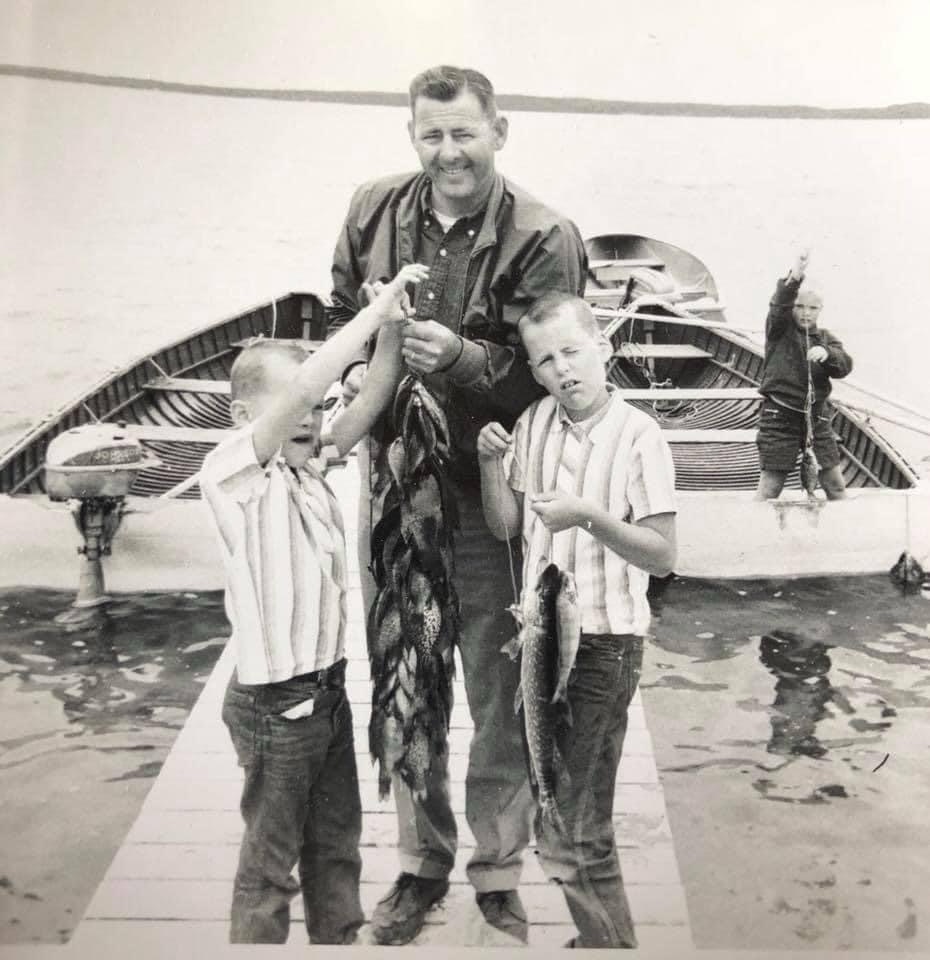

That Iowa farm boy, my grandfather Don Muhm, is the person who comes to mind when I consider the importance of giving students time, space, and encouragement to create. He was born in 1928 on a farm in Hancock County in rural Iowa. His parents struggled to farm profitably and he loathed the one pair of overalls that he had to wear. Don Muhm was educated in one room school houses before attending high school in Britt, Iowa where he graduated in 1946.

While writing in high school, Don Muhm’s talent caught the eye of a teacher who encouraged him to continue writing. He did. He wrote for the local town paper while still in high school and decided he wanted to be an agricultural journalist.

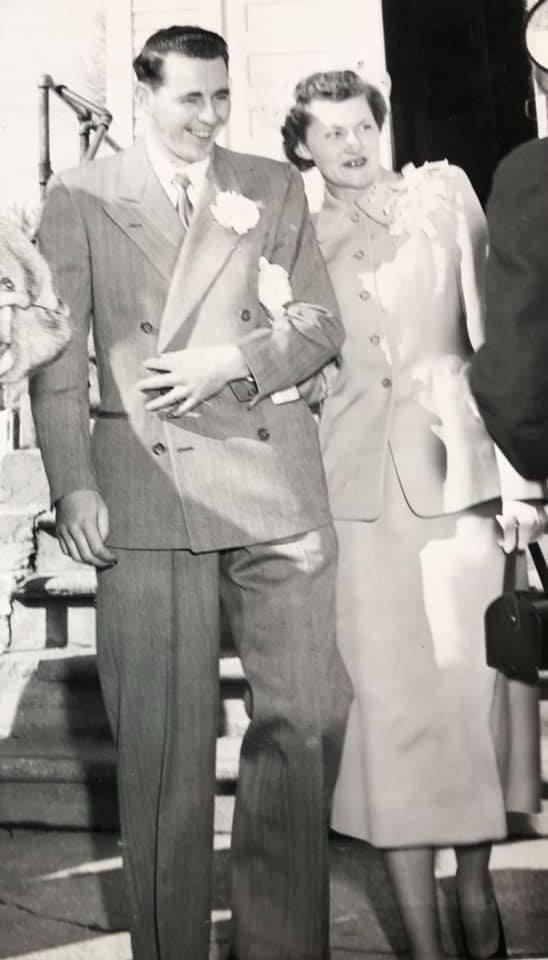

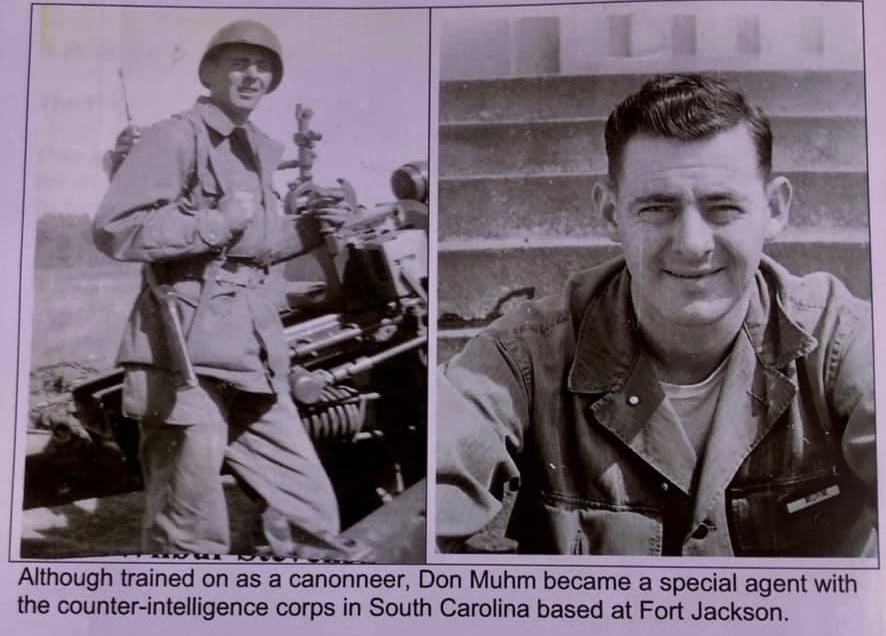

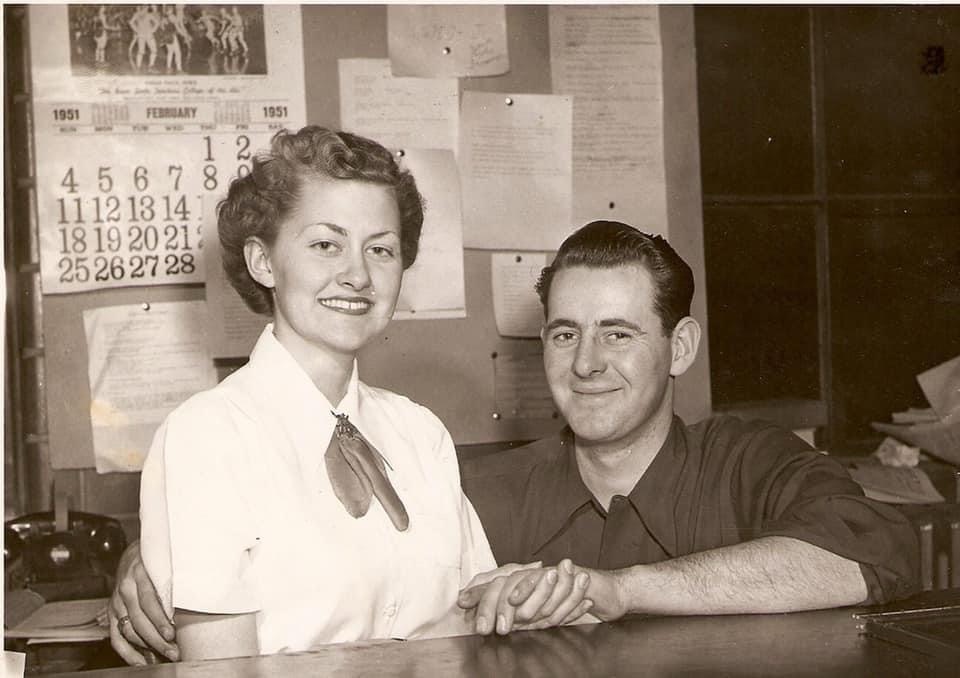

He went on to study journalism at Iowa State University, writing for the Iowa State Daily while attending college. Upon graduation, he married my grandmother, Joann Muhm and served in the U.S. Army. He was stationed in South Carolina and served in the intelligence unit. My grandma used to tell me stories about this time. How she loved the flowers in South Carolina but missed the four seasons of the midwest. How her neighbors were always nosy about her business. She’d laugh as she said grandpa would drive home in a different car each night as he was often doing surveillance and the neighbors all decided that grandma was a “tootsie” bringing different men home each night.

After discharge, Don Muhm went on to write. First at the Marshalltown Times-Republican then the Omaha World Herald as Farm Editor, where he won several awards. He then took a job at the Des Moines Register and Tribune as farm editor and wrote a column titled, “Country Living” where he wrote for thirty five years. He was also a prolific author who published ten books.

I think about Don Muhm often. His one room schoolhouse teachers didn’t have some expensive scripted boxed curriculum aligned to the common core standards with a fancy sticker claiming to incorporate the science of reading. They likely had a few good books, papers, inkwells, and slate boards. Yet Don Muhm, the poor Iowa farm boy with one pair of overalls, learned how to write and read well enough to make one heck of a career out of it.

ISU Agriculture Hall of Fame in 1967, the Glenn Cunningham Agriculture Journalist of the Year award in 1967, 1969, and 1978, U.S. Conservation Writer of the Year in 1973, and the J.S. Russell Memorial Award in 1974.

And how about that teacher that encouraged him. That gave him space to write. That gave their time to observe and notice his talent. That gave Don Muhm the encouragement to become the voice of agricultural journalism for decades. Let’s empower those teachers and trust their decision making.

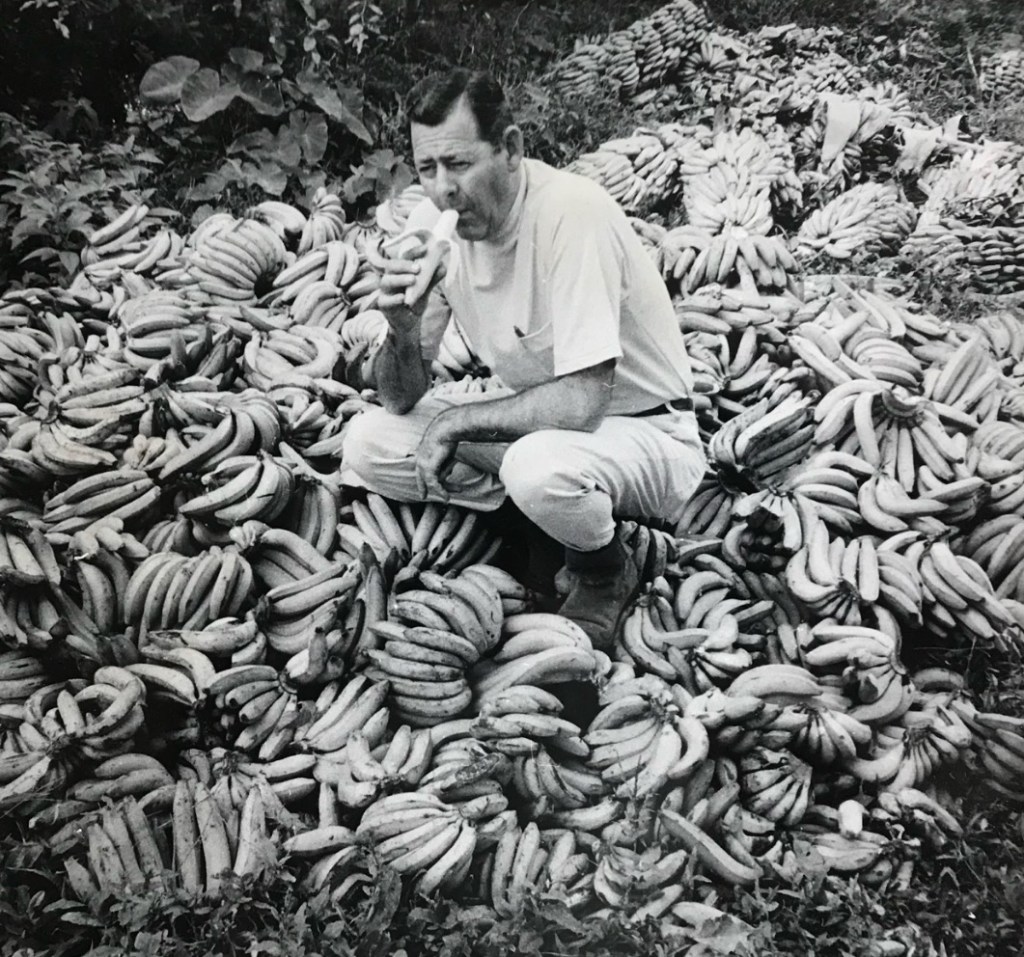

Grandpa Don Muhm saw a lot in his career. I remember his stories of the Peace Corps farm projects in South America in 1970. He stayed at a hotel where he struggled to communicate as an English speaker in a country of Spanish speakers. He asked the man carrying bags to please give him a wake up call at 7:00am. As they both didn’t understand the language of each other, my grandfather held up seven fingers and then held up his thumb. A lightbulb went off in the bellhop’s mind. He understood! He ran off.

An hour later, there was a knock on my grandfather’s room. He opened the door to see the bellhop proudly holding a silver tray with a bottle of 7-up. My grandfather laughed and laughed until he got an expensive room service bill the following morning.

My grandfather was a great supporter of my writing. He’d read my college papers and share his thoughts and pride that his granddaughter not only inherited his dark eyebrows and angular profile, but his love of writing as well. Those were special moments; sitting in his Des Moines living room or at the kitchen table of his cabin on Big Spirit Lake, sharing a generational love of words.

Those moments came to an end too soon. After a battle with Parkinson’s, my grandfather passed away in 2007 and I inherited his laptop. My grandma wanted me to have it on my travels to Germany.

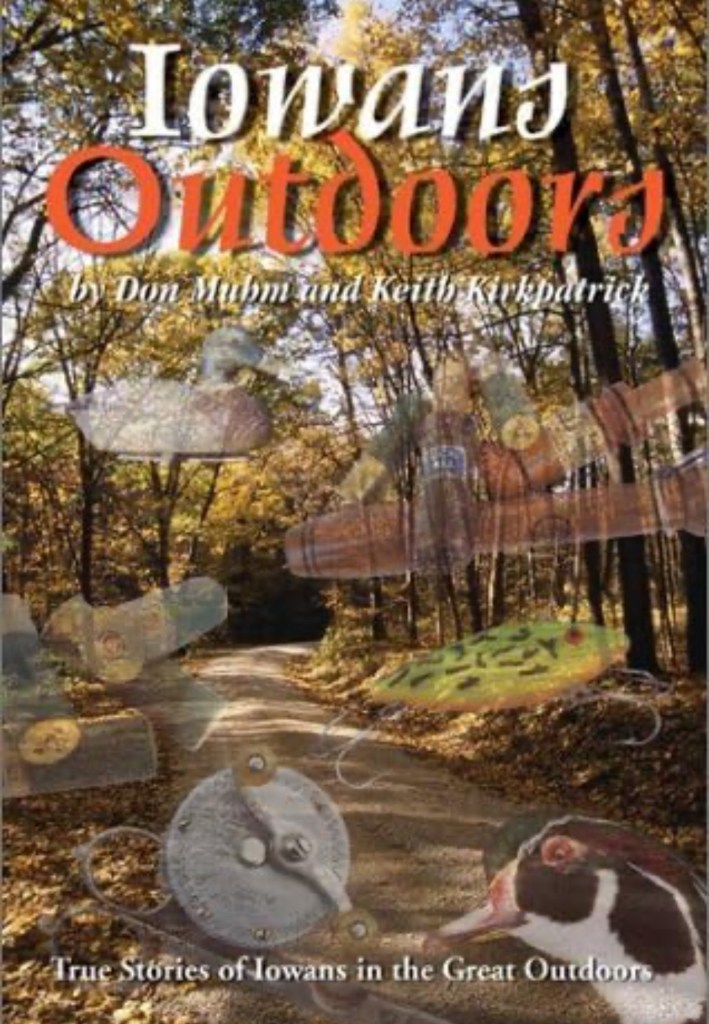

On his laptop was the manuscript for the last book he wrote, stories of our family’s military history. This was also the laptop used for writing a book of our family’s love of the outdoors. Coincidentally, my husband’s family is mentioned several times throughout this book and I used this same laptop to Skype with my future husband while overseas. My husband also kept my number on a piece of paper inside his copy of Iowans Outdoors when we first started dating.

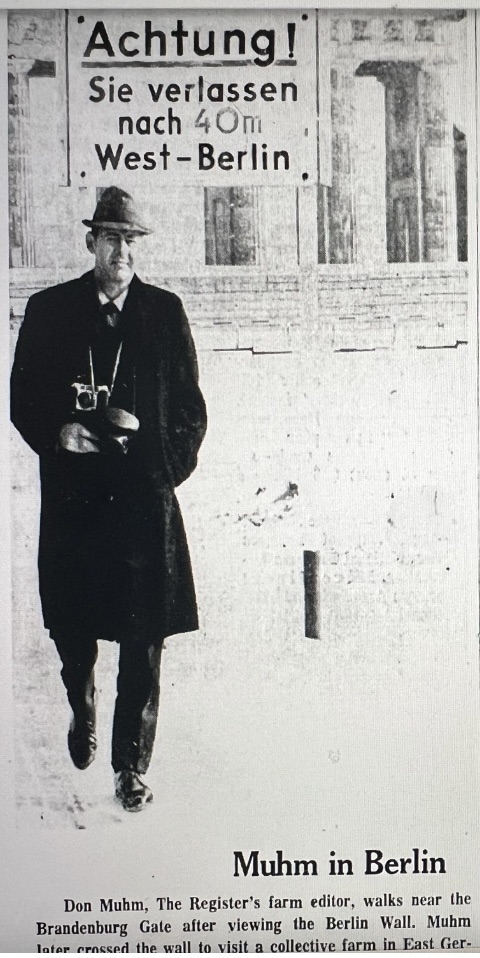

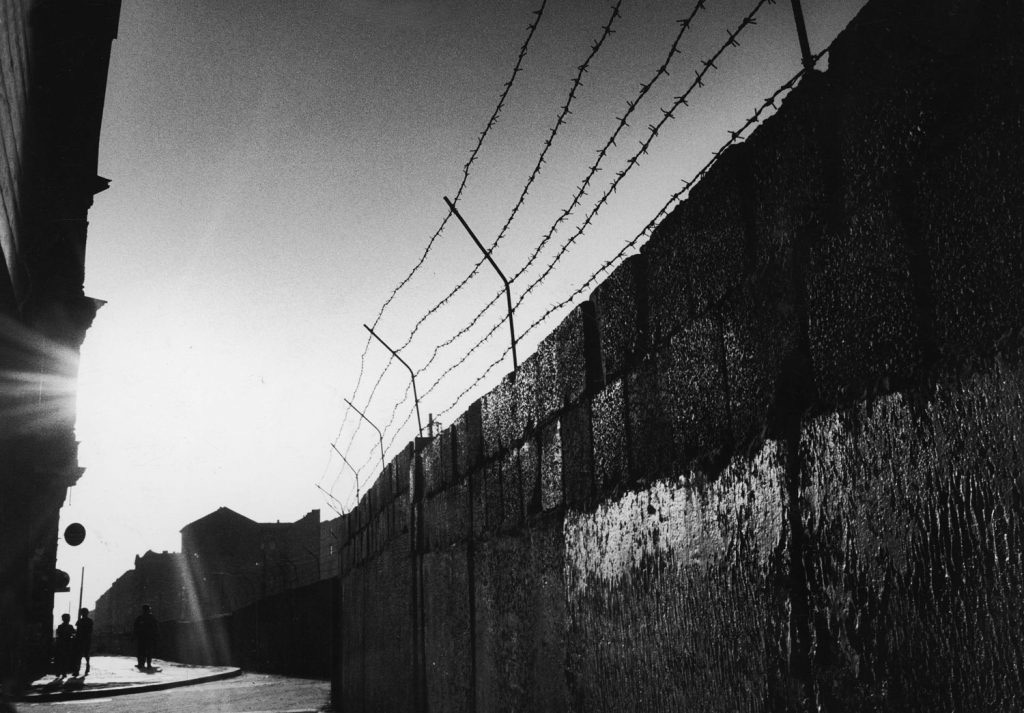

While working in Germany, I traveled to the Berlin Wall, standing where my grandfather had twice stood before as a journalist, covering stories of both the wall’s erection in 1961 and 1989 collapse.

I reread an article my grandfather had written when the wall was erected. An Iowa farm boy, he had seen plenty of barbed wire used to contain livestock. But he’d never seen it used to contain people and there was something deeply disturbing in treating humans as livestock.

His words stung and stuck like daggers dipped in alcohol; they were the very best words to depict the hell that is war.

And that’s what happens if we don’t hear the stories of others. If we silence their voices. If we ignore the lessons of the past. If we take away the time and space to create. Our differences, even things as pointless as which side of a city we reside, become the walls and barbed wire fences that tear apart families and escalate horrific violence. They strip us of our humanity and lead to unfathomable atrocities.

We can take down those walls, brick by brick. We can empower our learners to discover their talents and confidently create in a way no one before has created. We can create safe spaces for sharing stories and truly listen to the stories of others. We can bring the stories of others to our students through literature and meaningful conversations. We can be curious and empathize. We can see the humanity in everyone we meet and everyone we haven’t met.

We can teach our students that barbed wire is used to separate livestock, never humanity.

My grandfather loved people. He loved telling their stories. He loved helping the underdog and I can’t remember him ever passing the opportunity to stop when someone on the road’s edge was selling berries or corn or tomatoes. He’d stop and hear their story and then buy as much as we could carry. He’d talk to everyone and hear their story. And everyone would talk to him.

My father shares a story I adore. As a young girl, I loved visiting the Iowa State Fair with my grandfather. He would take us around the fairgrounds in a golfcart and we would stay at his cozy ranch home in West Des Moines where my grandmother always served delicious dinners with a cold glass of whole milk, a rare treat as my mother only bought skim. On one such trip, my older brother Casey and I attended the fair with my father Maury, mother Donna, and grandfather Don Muhm. As we were walking the midway, my mom saw Senator Tom Harkin, whom she had worked for while in college at Iowa State University in the 1970s. While chatting with Tom Harkin, my dad introduced his father Don Muhm. Tom Harkin then became engrossed in a conversation with my grandfather, much to the annoyance of his political aides who were trying to keep a busy schedule. After failed attempts to politely end the conversation, one of the aides said, “Senator, we have to go!” and Don Muhm and Tom Harkin were forced to end their captivating conversation.

Don was a good journalist because he connected with everyone. He looked for and saw the humanity in every single person he met. He told their stories to the other side of the world and reminded us of the power of words.

Words can connect a room full of educators who’ve only just met. Words can bring us to tears. Words can lift us up. Words can start wars. Words can end wars.

Words can convince a student of humble beginnings that they have what it takes to be a writer. Words can take a rural Iowa farm boy all over the world. And the words he brings back, can transcend generations.

Learn More About Donald Charles Muhm

Leave a comment